Understanding How to Use Tenses in a Research Paper

Verb Tenses in Research Papers: The Ultimate Guide to Mastering Academic Writing Standards

Writing a research paper demands far more than simply presenting your findings—it requires adherence to scholarly conventions that elevate clarity, readability, and professional credibility. Among these conventions, proper verb tense selection stands as a cornerstone of effective academic communication. When wielded correctly, tense usage illuminates the temporal landscape of your work, distinguishing between established knowledge and fresh contributions, completed actions and ongoing relevance. Every seasoned academic knows that mastering verb tenses in research papers transforms a decent manuscript into a compelling, publication-ready document.

Let’s dive into the nuanced world of tense usage across different sections, exploring practical examples and strategic insights that will sharpen your academic writing precision.

Why Do Verb Tenses Matter So Much in Scholarly Writing?

Imagine reading a peer-reviewed article where the verb tenses clash with the temporal context of the described research. That single inconsistency can ripple through the reader’s mind, casting doubt on the author’s methodological rigor. In academic discourse, each tense carries distinct rhetorical weight: the past tense signals completed investigations, the present tense frames eternal truths and current significance, and the future tense charts unexplored territories. This temporal precision separates rigorous scholarship from amateur composition.

The Link Between Tense Accuracy and Academic Authority

When you deploy tenses correctly, you silently signal to journal editors and reviewers that you understand the unwritten codes of scholarly communication. This becomes particularly critical when targeting high-impact journals where editorial scrutiny is unforgiving. Whether you’re in medicine, engineering, social sciences, or humanities, grammatical tense selection directly influences how reviewers perceive your methodological soundness and interpretive clarity. A manuscript riddled with tense inconsistencies often faces desk rejection before even reaching peer review.

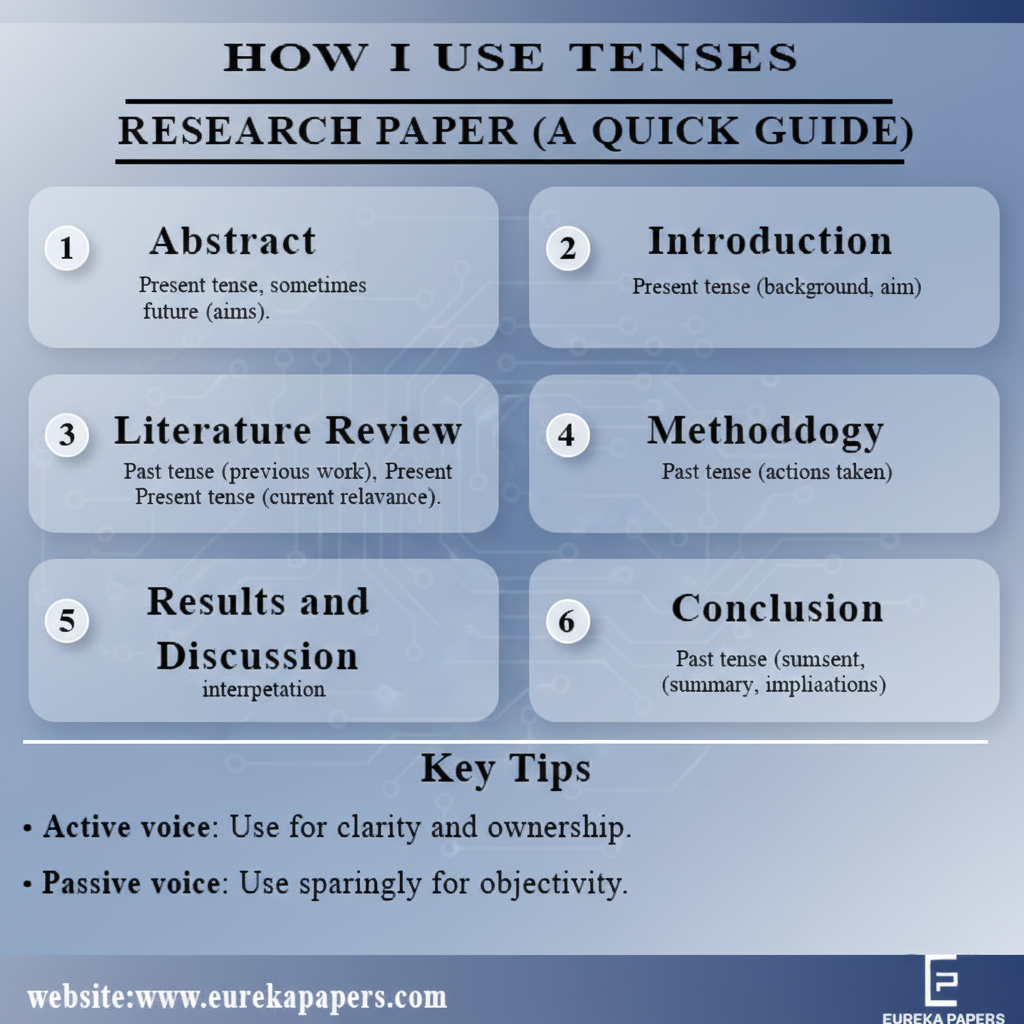

Abstract: The Art of Blending Present and Past Tenses

The abstract functions as your research’s elevator pitch—a condensed narrative that must hook readers instantly. Within this tight 150-250 word space, you’re juggling two temporal dimensions simultaneously.

Leveraging Present Tense for Research Relevance

Use the present tense to frame your study’s objectives, articulate research gaps, and emphasize the topic’s ongoing significance. This approach positions your work within the current scholarly conversation.

Example: “This study examines the cascading effects of microplastic pollution on estuarine food webs.”

The verb “examines” in present tense declares that your research addresses a living, breathing scientific question. It tells readers, “This matters right now.”

Deploying Past Tense for Methodological Rigor

Shift to past tense when summarizing completed procedures and key findings. This temporal shift provides concrete evidence that your investigation is finished and your conclusions are data-driven.

Example: “Satellite imagery was processed to quantify habitat fragmentation, and statistical modeling revealed a 34% decline in biodiversity indices.”

Here, “was processed” and “revealed” anchor your claims in completed actions, lending empirical weight to your abstract’s promises.

The magic lies in this deliberate oscillation: present tense sells the importance, past tense delivers the proof. Together, they create a compelling snapshot that balances ambition with credibility.

Introduction: Where Temporal Boundaries Collide

Your introduction serves as the scholarly stage where past discoveries meet present imperatives. The strategic deployment of verb tenses here guides readers through your field’s intellectual history toward your unique contribution.

Present Tense for Established Knowledge

When referencing undisputed facts, widely accepted theories, or the current state of understanding, present tense reinforces their enduring validity.

Example: “Climate change represents the defining challenge of our era, threatening infrastructure resilience worldwide.”

The verb “represents” signals this as contemporary reality, not historical footnote.

Past Tense for Prior Research

Immediately switch to past tense when citing specific studies or historical investigations. This temporal marker distinguishes your work from the existing body of literature.

Example: “Smith et al. (2019) demonstrated that temperature anomalies correlate with increased infrastructure failure rates.”

The past tense “demonstrated” clearly positions this research in the completed past, creating space for your own contribution.

Active Voice: Claiming Your Scholarly Territory

Employ active voice to assert ownership of your research agenda and highlight your intellectual agency. This voice makes your prose direct and authoritative.

Example: “We address this critical gap by integrating socio-economic variables into predictive models.”

The active construction “We address” leaves no doubt about who is driving this scholarly intervention.

Passive Voice: When Process Trumps Personality

Sometimes the action itself deserves center stage, not the actor. Use passive voice sparingly in introductions to emphasize procedures over personalities.

Example: “A comprehensive meta-analysis was conducted to synthesize disparate findings.”

Here, the passive construction shifts focus to the analysis itself, which suits the context. But beware—overusing passive voice in introductions can make your writing feel detached and lifeless.

Literature Review: Mapping the Scholarly Terrain

Your literature review must skillfully navigate between what is currently accepted (present tense) and what has been previously discovered (past tense). This section constructs the intellectual map that situates your research.

Present Tense for Living Debates

Use present tense to discuss current trends, evolving theories, and ongoing scholarly conversations that remain vibrant and unresolved.

Example: “Contemporary research emphasizes the intersectionality of environmental justice and public health outcomes.”

The verb “emphasizes” suggests this is an active, developing discourse.

Past Tense for Completed Studies

When discussing specific investigations with defined timelines, past tense correctly positions them as historical contributions.

Example: “Rodriguez (2021) identified significant methodological limitations in cross-sectional studies of this phenomenon.”

The past tense “identified” signals that this critique exists in the scholarly record, awaiting your response.

The Subtle Power of Present Perfect

Occasionally, present perfect tense bridges past and present beautifully: “Scholars have increasingly recognized the role of indigenous knowledge systems.” This construction shows a trend that began in the past and continues today, adding temporal depth to your literature synthesis.

Methodology: The Domain of Passive Voice Constructions

In methodology sections, objectivity reigns supreme. Your personality fades as the research process takes center stage. Here, passive voice constructions—both present and past—become your primary tools.

Present Passive for Standard Procedures

Describe established, widely-used methods in present passive tense to present them as accepted protocols within your field.

Example: “Quality control is performed using validated calibration standards.”

The construction “is performed” frames this as a routine, replicable procedure.

Past Passive for Your Specific Actions

Switch to past passive tense to describe exactly what you did in your particular investigation, ensuring reproducibility.

Example: “Soil samples were collected from 0-15 cm depth using a stainless-steel auger, then frozen at -80°C until analysis.”

The past passive “were collected” and “frozen” provides a precise, impersonal account that any researcher could replicate.

Why this passive dominance? Because methodology sections must read like instruction manuals—clear, objective, and actor-agnostic. “Samples were analyzed” functions as a universal directive, whereas “We analyzed samples” introduces unnecessary subjectivity.

Results and Discussion: The Tense Interplay Dance

This section demands the most sophisticated tense management. You’re simultaneously reporting raw data (typically past tense) and interpreting its significance (present tense). This interplay creates a rich, multi-layered narrative.

Past Tense for Empirical Observations

Report specific measurements, observations, and experimental outcomes in past tense to anchor them in completed reality.

Example: “The treatment group exhibited a 47% reduction in symptom severity compared to controls.”

The past tense “exhibited” documents what actually happened during your investigation.

Present Tense for Interpretive Significance

Immediately shift to present tense when explaining what your findings mean and how they answer your research questions.

Example: “These results demonstrate that targeted intervention protocols yield superior clinical outcomes.”

The present tense “demonstrate” frames this conclusion as a current, generalizable truth emerging from your study.

Masterful Tense Combinations

Often, a single sentence braids both tenses: “While preliminary data showed no significant differences (past observation), deeper analysis reveals critical threshold effects (present interpretation).” This temporal layering shows readers you can move fluidly between description and analysis—a hallmark of mature scholarship.

Pro Tip: When discussing limitations, present tense often works best: “This limitation suggests that findings should be interpreted cautiously.” This frames the limitation as an ongoing consideration for readers.

Conclusion: Summarizing Past, Charting Future

Your conclusion must look backward to summarize achievements while projecting forward to suggest new horizons. This temporal pivot demonstrates both completion and continuity.

Past Tense for Achievement Recap

Summarize your main findings and contributions using past tense to emphasize their origin in completed work.

Example: “This investigation revealed novel interactions between urbanization patterns and avian community structure.”

The past tense “revealed” confirms these insights emerged from your finished study.

Future Tense for Research Horizons

Deploy future tense to propose next steps, indicating that your work opens doors rather than closes them.

Example: “Future studies will investigate the long-term evolutionary consequences of these urban-rural gradients.”

The future tense “will investigate” positions your research as a foundation for ongoing inquiry, not an endpoint.

This strategic combination shows you’re a forward-thinking scholar who understands that science is cumulative. You’re not just finishing a project; you’re launching a conversation.

Golden Rules for Active vs. Passive Voice Selection

The cardinal rule? Clarity trumps all. Choose the voice that makes your meaning most transparent and your argument most compelling.

When Active Voice Dominates

Use active voice to claim ownership, assert agency, and create engaging prose. It’s essential in introductions (where you stake your claim) and conclusions (where you summarize your intellectual contributions).

Example: “We propose a paradigm shift in how researchers conceptualize ecosystem resilience.”

This active construction establishes you as the agent of change.

When Passive Voice Shines

Embrace passive voice when the process or object of action matters more than the actor. It’s particularly valuable in methodology and when acknowledging limitations.

Example: “The theoretical framework was evaluated against empirical benchmarks.”

Here, the passive construction keeps focus on the framework, not the evaluator.

Critical Insight: Many early-career researchers overuse passive voice, thinking it sounds more “academic.” The opposite is true—strategic use of active voice makes your writing more confident and readable.

Common Tense Mistakes and How to Eliminate Them

One pervasive error involves using present tense for completed research actions. Writing “The data shows” instead of “The data showed” in your results section inadvertently suggests your study remains unfinished—a credibility killer.

Another frequent blunder: using past tense for universal truths. “Newton discovered that gravity was a force” misplaces gravity in history, whereas “Newton discovered that gravity is a force” correctly preserves its timeless reality.

Your Self-Editing Mantra: Before writing any verb, pause and ask: “Is this a timeless fact or a completed action? Is this an interpretation that lives in the present or an observation that belongs to the past?” This simple habit corrects 90% of tense errors instantly.

Disciplinary Nuances in Tense Conventions

Verb tenses in research papers aren’t monolithic. Social sciences and humanities often favor present tense to emphasize interpretation and theoretical framing. Natural sciences and engineering lean more heavily on past tense for methodology and results, privileging empirical documentation. Medical sciences frequently use present tense for clinical significance and past tense for procedural details.

Strategic Move: Before drafting, examine 3-4 recent articles from your target journal. This reconnaissance reveals the publication’s stylistic DNA, helping you align your tense usage with editorial expectations.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Can I ever use present tense in the methodology section?

Yes, but restrict it to describing standard, widely-accepted procedures. For example: “DNA extraction is performed using the Qiagen DNeasy kit.” This present passive construction frames the method as a field-wide protocol. However, for your specific modifications or unique steps, always use past passive: “Samples were processed using our novel filtration technique.” This distinction separates universal methods from your particular application.

2. How do I choose between active and passive voice in the discussion section?

In discussion sections, active voice strengthens interpretive claims: “We argue that these findings fundamentally challenge existing paradigms.” This asserts your intellectual authority. Use passive voice when comparing your work to others: “Similar trends were observed in previous longitudinal studies.” This keeps focus on the trends, not the researchers. Remember: active voice for ownership, passive for objectivity.

3. Is using future tense in the introduction ever acceptable?

Generally, avoid it. Instead of “This study will examine…” use the more decisive present tense: “This study examines…” Save future tense for your conclusion’s forward-looking suggestions. Using present tense in the introduction demonstrates confidence that your research is already contributing, not merely promising to contribute later.